Note: This article was originally published at TheNationalPastimeMuseum.com on April 24, 2017, and is reprinted here by permission.

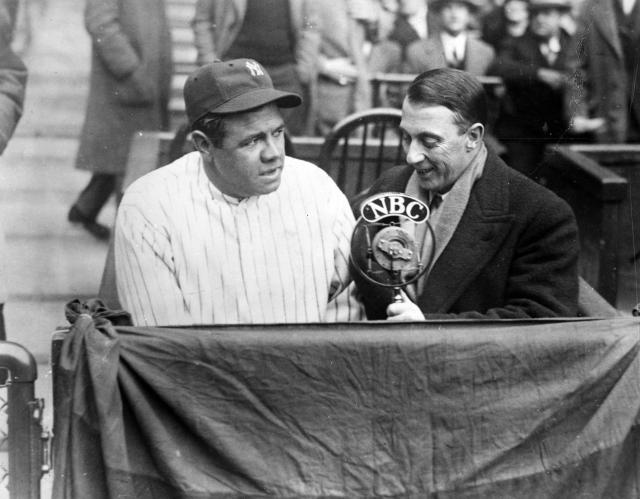

Baseball broadcasting pioneer Graham McNamee was honored with the Ford C. Frick Award in 2016. (Library of Congress)

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen of the radio audience!”

Long before Vin Scully, Walter Cronkite, or Ernie Pyle became household names, Graham McNamee was the most famous broadcaster in the world. In the earliest days of radio during the twentieth century, McNamee’s distinctive introduction was the cue for millions of Americans to gather around their household sets and listen to the most exciting events of the day.

When the Baseball Hall of Fame announced that McNamee had been selected as the recipient of the 2016 Ford C. Frick Award honoring excellence in baseball broadcasting, the most common reaction from fans and writers was “wait . . . who’s that?” But no discussion of baseball broadcasting can begin without him.

McNamee’s rise to fame was so sudden and his fall from the public eye so complete that it’s hard to believe what a big star he was in the 1920s and ’30s. That was the first golden era of American sports, dominated by legends like Babe Ruth in baseball, Red Grange in football, Jack Dempsey in boxing, Bobby Jones in golf, and Bill Tilden in tennis. To most fans, McNamee was the common thread tying all of these great athletes together, sitting behind the microphone to describe their historic feats.

McNamee called 12 World Series, appeared on the cover of Time magazine, and invented play-by-play broadcasting all by himself. His dramatic, rapid-fire descriptions of sporting events, political conventions, and news in real time entertained and informed his audience in ways that could scarcely have been imagined just a few years earlier, before commercial radio even existed. Contemporary scientists estimated that McNamee’s voice was heard by more people than any other human being in history.

“Nobody had ever been called upon before to do such work. They had to go out and do it from scratch,” wrote Red Barber, who was the first broadcaster—along with Mel Allen—to receive the Frick Award. “If ever a man did pure, original work, it was Graham McNamee.”

When aviator Charles Lindbergh returned from Paris after his record-setting flight across the Atlantic Ocean, McNamee described his ticker-tape parade on NBC radio. When Calvin Coolidge was inaugurated as president of the United States, McNamee was in the nation‘s capital narrating the ceremony. When Jack Dempsey knocked down Gene Tunney in the controversial “Long Count” heavyweight championship fight, McNamee was in the front row calling the action.

He was everywhere. And for nearly two decades, everyone listening in hung on his every word. Nobody brought the country together quite like the animated Minnesotan with the baritone voice who had studied to be an opera singer.

We marvel today at the wireless technology that allows us to watch just about any sporting event live and on demand in the palm of our hands. But a century ago, it was the revolution of radio that first made the world seem small, enabling fans in San Francisco to hear the sound of a ball game being played in New York as it was happening. Radio made Major League baseball more accessible to the common fan, and no one represented the fan more than McNamee did behind the mic.

McNamee‘s influence on baseball broadcasts can still be widely felt today. If you find your heart racing as Jon Miller breathlessly describes a thrilling ninth-inning home run for the Giants, you should know McNamee pioneered that style of announcing. If you‘ve laughed along with Ralph Kiner’s endearing malapropisms in the Mets booth, well, McNamee was doing that first, too.

“Because the great majority of listeners wish to be transported to the scene, the unimportant details must be sacrificed for the human touch,” McNamee explained. “My task is to give the listener all the color, the gayety, and the intensity of the game.”

Boy, did he ever. McNamee was known for his dramatic delivery, raising his voice during the game’s most dramatic moments, a fan-friendly style that begat popular broadcasters such as Harry Caray, Bob Prince, and Jack Brickhouse in later years. He would occasionally take a brisk walk between innings so that he would return to the booth slightly out of breath.

He also made his share of mistakes; nobody could ever be too sure if what McNamee had described was actually what happened on the field. He sometimes forgot which teams were playing or failed to give the score for a few innings. As the humorist Ring Lardner once wrote, “There was a doubleheader yesterday—the game that was played and the one McNamee announced.” And thus, he also became the first national announcer that baseball fans liked to complain about, a tradition carried on to the present day by the likes of Joe Morgan, Tim McCarver, and many others.

You have to cut McNamee a little slack for his miscues; after all, he had no sports background, no news background, and no radio background when he was thrust into his high-profile role during the middle of the 1923 World Series. He had only gotten his job at WEAF (which later became NBC) in New York when he wandered in to the station while on a lunch break from jury duty and asked for an audition as a singer. They hired him to answer phones for $50 a week, but because of his powerful voice, someone got the wise idea to put him on the air instead.

Baseball had been broadcast experimentally for the first time in 1921, when a foreman for Pittsburgh’s KDKA station used a jury-rigged telephone to call a game from a box seat at Forbes Field. That was also the year of the first World Series broadcast, again through KDKA, with syndicated newspaper columnist Grantland Rice at the mic. Rice was never comfortable in the role, and by 1923 he was begging out of his broadcasting duties, as the New York Giants and New York Yankees met in the Series for the third straight year.

That set the stage for McNamee, who was simply in the right place at the right time. WEAF hired another sportswriter, W. O. McGeehan, to serve as lead announcer, and McNamee was assigned to be his assistant. In the fourth inning of Game 3, McGeehan suddenly walked off the job and handed his microphone to McNamee, whose only real experience in sports was calling a middleweight championship boxing match. But he proved to be a natural, and fans loved his energetic style, even if he happened to embellish some of the details. Regrettably, his call of Casey Stengel’s game-winning home run that day has been lost to history.

A few weeks later, McNamee called the Army-Navy football game, and in the summer of 1924, the Republican and Democratic National Conventions, where he first became a household name. For two straight weeks, for nearly 16 hours a day, McNamee described the dramatic deadlock between Democratic presidential candidates Al Smith and William Gibbs McAdoo for listeners around the nation. By the time the World Series began, he was a celebrity, and an estimated audience of nearly three million people tuned in to hear him call Walter Johnson and the Washington Senators’ triumph over the Giants.

Graham McNamee interviews Babe Ruth of the New York Yankees before a World Series game in the 1920s. (BaseballHall.org)

But once the novelty of radio began to wear off after a few years, McNamee’s flaws at the mic became more noticeable. Hollywood films parodied him as a bumbling announcer who didn’t know what he was watching. In the 1929 Rose Bowl, University of California lineman Roy Riegels picked up a fumbled football and ran the wrong way down the field toward his own goal line, a monumental blunder that cost Cal the game. On the radio, McNamee gave an accurate description of the strange play but many listeners assumed that he was confused as to which team had the ball again.

By the mid-1930s, McNamee’s star had been surpassed by the likes of Red Barber in Cincinnati, Ty Tyson in Detroit, and Bob Elson in Chicago—the latter of whom had been personally selected by baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis to replace McNamee as the World Series lead announcer for NBC. These broadcasters emulated the high energy that was McNamee’s trademark, but brought a more sophisticated knowledge of the game that endeared them to baseball fans for years to come. Whereas McNamee had no predecessors, they had the benefit of McNamee as a role model.

“He had no experience, no help,” Barber wrote. “Everything has to have its beginning. He was the first. . . . There never was such a voice of excitement heard as that of Graham McNamee.”