This article was published in the SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee’s June 2024 newsletter. A section about Bowie Kuhn’s suspensions of Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays has been corrected from the original version.

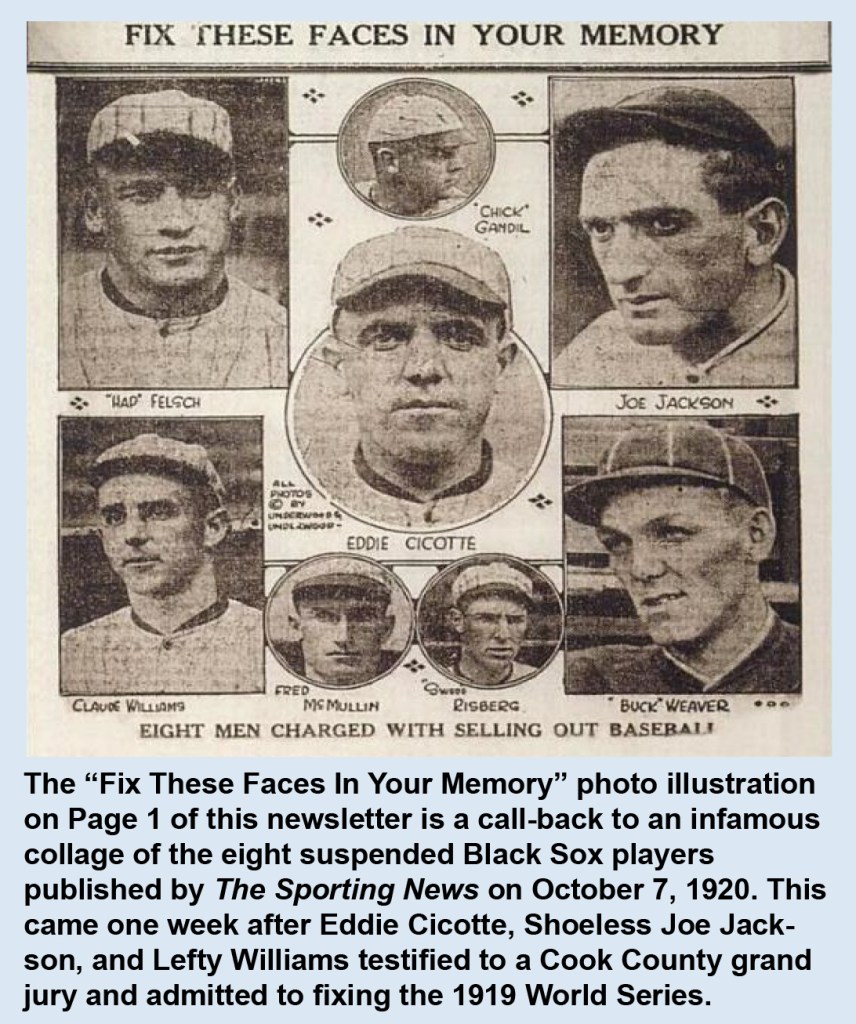

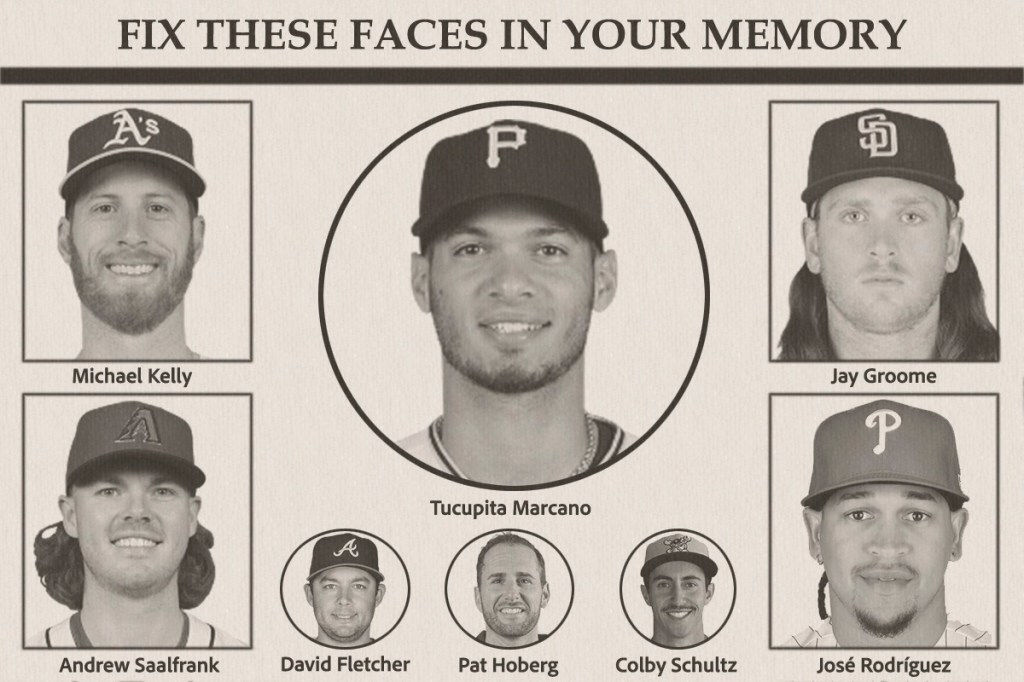

The 2024 baseball season has been plagued by gambling scandals. On June 4, Tucupita Marcano was permanently banned for placing bets on Pittsburgh Pirates games while he was with the team and four other players were suspended for one season for betting on major-league games. In addition, umpire Pat Hoberg, former MLB player David Fletcher, and Colby Schultz are all under investigation for gambling-related incidents. (Photos: MLB.com. Illustration: Jacob Pomrenke)

Baseball’s Rule 21 hasn’t changed much since Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis first proposed it nearly a century ago in the wake of a gambling scandal involving future Hall of Famers Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker.1

If you are employed by a professional baseball team or league, you cannot place a bet on the sport without risking a one-year suspension. If you bet on your own team — to lose or even to win — you will be permanently banned. The same lifetime punishment applies if you agree to intentionally lose a game in which you have a duty to perform.

Rule 21 is posted inside every major-league clubhouse, where all players, coaches, umpires, and staff members can see it any time they arrive at the ballpark. It has long been considered the one cardinal rule that everyone in the game must follow. Even Pete Rose.

In 2024, a new generation of players finds itself in the cross-hairs of Rule 21.

On June 4, former Pittsburgh Pirates infielder Tucupita Marcano was issued a lifetime ban by Commissioner Rob Manfred after a Major League Baseball investigation determined that he placed 387 baseball bets between October 2022 and November 2023 — including 25 bets on Pirates games while he was on the team’s major-league roster. Marcano was on the injured list at the time and receiving medical treatment at PNC Park when he placed the bets; he did not appear in any of those games.2

Four other players were also handed one-year suspensions for betting on baseball: Oakland A’s pitcher Michael Kelly and minor-leaguers Jay Groome (San Diego Padres organization), Jose Rodríguez (Philadelphia Phillies), and Andrew Saalfrank (Arizona Diamondbacks). According to the MLB investigation, each of those players placed bets on major-league games while they were on minor-league rosters.

They are the first players to be punished under baseball’s Rule 21 since the US Supreme Court in 2018 struck down a federal law, the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, that paved the way for legalized sports gambling. As of 2024, nearly 40 states now have some form of legalized sports betting, either online or in-person or both. New sportsbooks have opened next door to Wrigley Field in Chicago, Great American Ball Park in Cincinnati, Chase Field in Phoenix, and other stadiums. MLB’s official television network displays live betting odds on a scrolling ticker every day and promotes parlay opportunities with its official betting partners.3

With sports gambling so easy to access for almost any adult in America with a smartphone and a bank account, it’s not hard to see how baseball players and team or league employees are getting caught up in betting scandals that spiral out of their control. No matter how many times they read or hear about Rule 21 — and the line they are continually reminded they are not allowed to cross while working in baseball — the temptation to place a bet and ruin a career can often prove impossible to resist.

Los Angeles Dodgers slugger Shohei Ohtani made headlines earlier this year when news broke that his trusted former interpreter, Ippei Mizuhara, admitted to stealing more than $16 million from Ohtani to pay off his gambling debts with an illegal bookmaker. MLB officials cleared Ohtani of any personal involvement in Mizuhara’s scheme, but the proximity of baseball’s biggest star in a gambling scandal of this scope surely must have given the game’s leadership nightmares about the Black Sox and Pete Rose.

David Fletcher, a former teammate of Ohtani’s with the Los Angeles Angels and now a minor-leaguer in the Atlanta Braves organization, is currently under investigation for placing bets with the same illegal bookie used by Mizuhara. Fletcher is not known to have bet on baseball. But his close friend Colby Schultz, a former minor-leaguer in the Kansas City Royals organization, did reportedly wager on baseball, including Angels games when Fletcher was on the team, according to a May 20 report by ESPN.4

In June, The Athletic reported that umpire Pat Hoberg was disciplined by MLB for violating the league’s gambling rules. Although it is unclear which section of Rule 21 he might have crossed, Hoberg has not appeared in a game this season while an appeal is considered by the league.5 Hoberg was promoted to MLB as an umpire in 2017 and has earned a strong reputation for accuracy after calling a “perfect” game of balls and strikes behind the plate during the 2022 World Series.

All of these recent incidents involve team or league employees betting on baseball, which is easier to do now than ever before. However, Rule 21 covers many other crimes of misconduct, too. It is important to distinguish between gambling and game-fixing, even though in certain situations they may carry the same punishment — a lifetime ban. Tucupita Marcano, like Pete Rose before him, was not accused of the same crime as the Black Sox. Marcano was banned for placing wagers on his own team’s games. The Black Sox were banned for accepting bribes to intentionally lose games. While one transgression can often be connected with the other, they are very different in scope.

Some media reports (including ESPN, NBC News, and the Associated Press6) claimed Marcano was the first active major league player in 100 years to be banned under baseball’s gambling provision. Those reports cited the case of New York Giants outfielder Jimmy O’Connell in 1924. But O’Connell was not banned for betting on baseball, either — he was punished for offering a bribe to an opposing player and attempting to fix a game.7

Rule 21(a) — in a section titled “Misconduct in Playing Baseball” — warns players “who shall promise or agree to lose, or to attempt to lose, or to fail to give his best efforts towards the winning of any baseball game with which he is or may be in any way concerned.” This section of the rule covers the fixing or attempted fixing of games, which would have ensnared the Black Sox following their loss in the 1919 World Series. The punishment for fixing games is a lifetime ban, then and now.

Rule 21(d) — in a section titled “Gambling” — targets any “player, umpire, or Club or League official or employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game.” Any bets placed on a game “with which the bettor has no duty to perform” shall cause that person to be declared ineligible for one year. Any bets placed on a game “with which the bettor has a duty to perform … shall be declared permanently ineligible.”8 That’s the rule which applied to Tucupita Marcano and the four minor-leaguers who were suspended.

Nearly a century ago, a scandal involving Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker — which precipitated the creation of Rule 21 in the first place — did involve the attempted fixing of a game and placing wagers on a game in which those star players had “a duty to perform.”

Cobb and Speaker, along with Smoky Joe Wood, were accused by a former teammate of attempting to fix a game between their own teams, the Detroit Tigers and the Cleveland Indians, at the end of the 1919 regular season. Their goal was to help Cobb’s Tigers win the game and earn a bonus for finishing in third place in the American League standings. Cobb and Wood wrote letters afterward about how they tried to also place bets on the game they had agreed for the Tigers to win.9

When the incident was made public years later, Judge Landis immediately called the players in to his office for a hearing. After the accuser failed to show up, Landis reluctantly cleared Cobb and Speaker, who were still active major-leaguers, and allowed them to continue playing. Then he proposed a new rule to put a stop to all incidents of gambling or game-fixing. Today, Rule 21 uses much of the Landis’s original language — and the same levels of punishment that he called for.

In addition to game-fixing and gambling, Rule 21 also includes separate provisions about offering gifts or bribes to opposing players (section “b”); gifts or bribes to umpires (section “c”); physical violence by or against umpires (section “e”); and conduct not in the best interests of baseball (section “f”).

It was Rule 21(f) that Commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti used to issue a lifetime ban to Pete Rose in 1989, following a series of negotiations between MLB’s lawyers and Rose’s representatives. Under the terms of Rose’s agreement, MLB did not make any formal findings on whether Rose bet on baseball, or bet on Cincinnati Reds games specifically. Instead, Giamatti banned Rose under the “best interests of baseball” clause.10 (An investigative report prepared by John Dowd11 for the Commissioner’s Office included extensive evidence that Rose did indeed bet on Reds games, both as a player and as a manager; Rose finally admitted to betting on baseball decades later.)

In fact, until Marcano’s punishment was levied, not a single active major-league player has been banned for life under Rule 21(d) — betting on your own team’s games — since it was officially approved in 1927. It is a punishment that is unprecedented in the history of baseball. But given today’s climate of sports gambling, Marcano may not be the only active player on that list for long.

That’s not to say other players haven’t bet on their own games. Many players have, especially in the days before the Black Sox Scandal, when betting on your own team was a more common and accepted practice. As The Sporting News once wrote about Hal Chase — the most corrupt player of the early 20th century — who was frequently accused of betting on and attempting to fix games: “When a player bets honestly on his own club, he’ll surely do his best to win, but it is a bad practice just the same.”12

At least one baseball executive has been banned under Rule 21(d), though. William D. Cox, owner of the Philadelphia Phillies, was thrown out of baseball by Judge Landis less than a year after purchasing the club in 1943. Cox’s first move after taking over the Phillies was to hire future Hall of Fame manager Bucky Harris. But in July, he abruptly fired the popular manager. Harris “had become aware that Cox was routinely betting” on Phillies games and he quietly went to Landis with that information.13 Landis launched an investigation, confirmed that Cox had placed approximately 15 or 20 bets ranging from $25 to $100 each on the Phillies to win, and confronted Cox with his findings after the season ended.

Cox attempted to circumvent the fallout by resigning from the Phillies’ board and promising to immediately sell the club. He claimed the bets were “small and sentimental” and they were made before he knew about Rule 21. But Landis went public with the news in November and announced he was banning Cox from ever holding another job in baseball.14

Rule 21(f) — the best interests of baseball clause — has been invoked several times to stop baseball figures from associating with gamblers. Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher was suspended by Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler for the entire season in 1947 (missing Jackie Robinson’s historic National League debut) because of his longstanding ties to gamblers and underworld mob figures.15 In 1970, Detroit Tigers ace Denny McLain was suspended by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn for 90 days after a Sports Illustrated article revealed his involvement in a Michigan bookmaking operation.16

In 1979, Kuhn used Rule 21(f) to terminate the employment contracts of Hall of Famers Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle after they were hired to provide public relations services by casinos in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Kuhn’s decision — which was widely reported as a lifetime ban, even though the commissioner made it clear the two stars would immediately be welcomed back to baseball as soon as they “disassociated” themselves from the casinos — was roundly criticized. The players’ “bans” were lifted a few years later by Kuhn’s successor, Peter Ueberroth.

In 1990, Commissioner Fay Vincent also invoked Rule 21(f) to permanently ban New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner for his dealings with a gambler he paid to spy on his star player, Dave Winfield.17 Steinbrenner’s ban was also lifted two years later.

None of those cases, however, involved players, or even team officials, betting on their own games. Perhaps Major League Baseball’s punishment of Tucupita Marcano and the four minor-league players accused of betting on baseball will serve as a deterrent for others in the future, just as Judge Landis set an example of the Black Sox players and effectively cut off the scourge of game-fixing that plagued the sport before and after the 1919 World Series. Or perhaps this is only the beginning of a new wave of Rule 21 infractions, nearly 100 years after it was established.

NOTES

1 Rule 21 can be found online at http://content.mlb.com/documents/8/2/2/296982822/Major_League_Rule_21.pdf

2 Mark Feinsand, “MLB announces sports betting suspensions for 5 players,” MLB.com, June 4, 2024.

3 Chelsea Janes, “MLB embraced gambling while trying to preserve its integrity. It’s a big bet.” Washington Post, June 9, 2024.

4 T.J. Quinn, “MLB opens investigation into David Fletcher gambling allegations,” ESPN.com, May 20, 2024.

5 Ken Rosenthal and Evan Drellich, “MLB umpire Pat Hoberg disciplined for violating gambling rules,” The Athletic, June 14, 2024.

6 “Tucupita Marcano gets lifetime MLB ban for betting on baseball,” ESPN.com, June 4, 2024; David K. Li, “MLB hits Tucupita Marcano with lifetime ban for betting on baseball games,” NBC News, June 4, 2024; Ronald Blum, “MLB bans Tucupita Marcano for life for betting on baseball, four others get one-year suspensions,” Associated Press, June 4, 2024.

7 For further analysis of Jimmy O’Connell’s lifetime ban, see Lowell Blaisdell, “Mystery and Tragedy: The O’Connell-Dolan Scandal,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 11 (1982).

8 For the record, Rule 21(b) concerns players who offer a “gift” to another team as a reward or bribe, similar to the 1917 White Sox in their disputed Labor Day series against the Detroit Tigers. That punishment warrants a three-year suspension. Rule 21(c) involves offering a gift or reward to an umpire for “services rendered”; that act would also result in a lifetime ban.

9 John Thorn, “Cobb & Speaker & Landis. Closing the Books.” 1927: The Diary of Myles Thomas, ESPN.com, May 17, 2016.

10 The Rose-Giamatti agreement released on August 23, 1989, can be found online at Baseball-Almanac.com at https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/p_rosea.shtml. The negotiations are covered in detail in Keith O’Brien, Charlie Hustle: The Rise and Fall of Pete Rose, and the Last Glory Days of Baseball (New York: Pantheon Books, 2024.)

11 The Dowd Report, which was provided to the Commissioner’s Office on May 9, 1989, can also be found online at Baseball-Almanac.com at https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/p_rose0.shtml.

12 W.A. Phelon, “Pulling for Chase to Clear Himself,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1918: 2.

13 Daniel E. Ginsburg, The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1995): 217-220.

14 “Owner Of Phils Is ‘Purged’ By Baseball’s Czar,” Toronto Star, November 23, 1943: 12.

15 Jeffrey Marlett, “The Suspension of Leo Durocher,” in Lyle Spatz, ed., The Team That Forever Changed Baseball and America: The 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2013).

16 Ginsburg, 231-234.

17 Murray Chass, “Steinbrenner’s Control of Yanks Severed,” New York Times, July 31, 1990.